Comprehensive academic workflow from reading to writing in markdown

Last update: 20. December 2021

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The Academic Workflow from Reading to Writing

- Overview: tools for the individual sub-tasks

- 1. Organizing references

- 2. Saving References

- 3. Linking PDFs, Reference Entries, and Citations

- 4. Extracting Annotations/Notes From PDFs

- 5. Citation Picker for Automatic Citations

- 6. Bibliography Creation

- 7. Compiling Markdown with Citations (Pandoc)

- 8. Bonus: organizing longform writing

- My own Implementation of the Workflow

Introduction

This is an overview over a comprehensive academic workflow, from getting annotations into Obsidian to writing a publication with Pandoc citations in Obsidian as well. There has already been a detailed description of how to achieve this with Zotero and MDnotes.

The workflow I describe here deals with very much the same problems, but takes a different direction. The goal of this post is, however, not to provide a step-by guide for implementing a workflow with certain apps or plugins. Rather, this post will discuss a general workflow for academic work which can be implemented with a variety of tools. Basically, one goal of this post is not to explain how to use certain tools, but rather to explain what the tasks are you should be using software tools for. And, of course, how to structure the individual tasks in such a way that everything works with minimal friction. The other goal of this post is to provide an overview of tools that can be used to accomplish those tasks. The overall intention is to give readers the autonomy to choose their own set of tools to customize their individual workflow.

First, I will outline the Academic Workflow from Reading to Writing in general and how to how it is implemented in different workflows by the average user and by the advanced Zotero user. Then, I will briefly outline my implementation and discuss why I do not use Zotero for it.(Disclaimer: I haven’t used Zotero 6.) I will end with an extensive overview of several tools (apps, plugins) that together provide comparable features.

The academic workflow from reading to writing

The generalized version

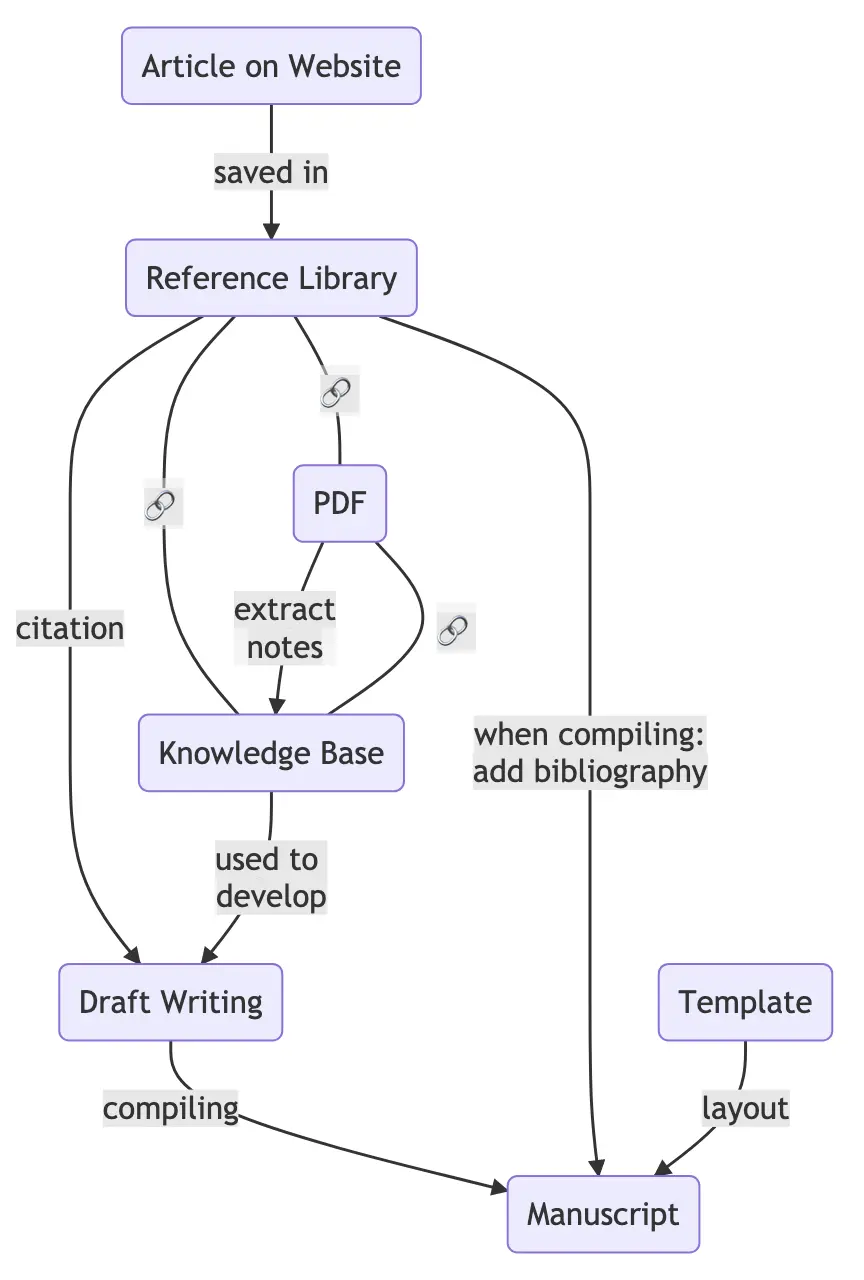

This basic academic workflow looks something like this: You find an article on a website, and save it in your reference library (i.e., reference manager). The library entries should be linked to the PDF file of the paper, from which we want to extract notes to our knowledge base (i.e., Obsidian). Ideally, we want to keep the link between library entry, knowledge base, and PDF.

Later on, you use your knowledge base to write an article of your own. When you cite a paper you have read, you basically create a link between the Draft and the entry in your reference library. During the final compiling of finished draft, the citations are used to add the bibliography to the finished manuscript. Ideally, you also use a template to save the time of creating a new layout every time you write a paper.

The simple Word-Zotero version

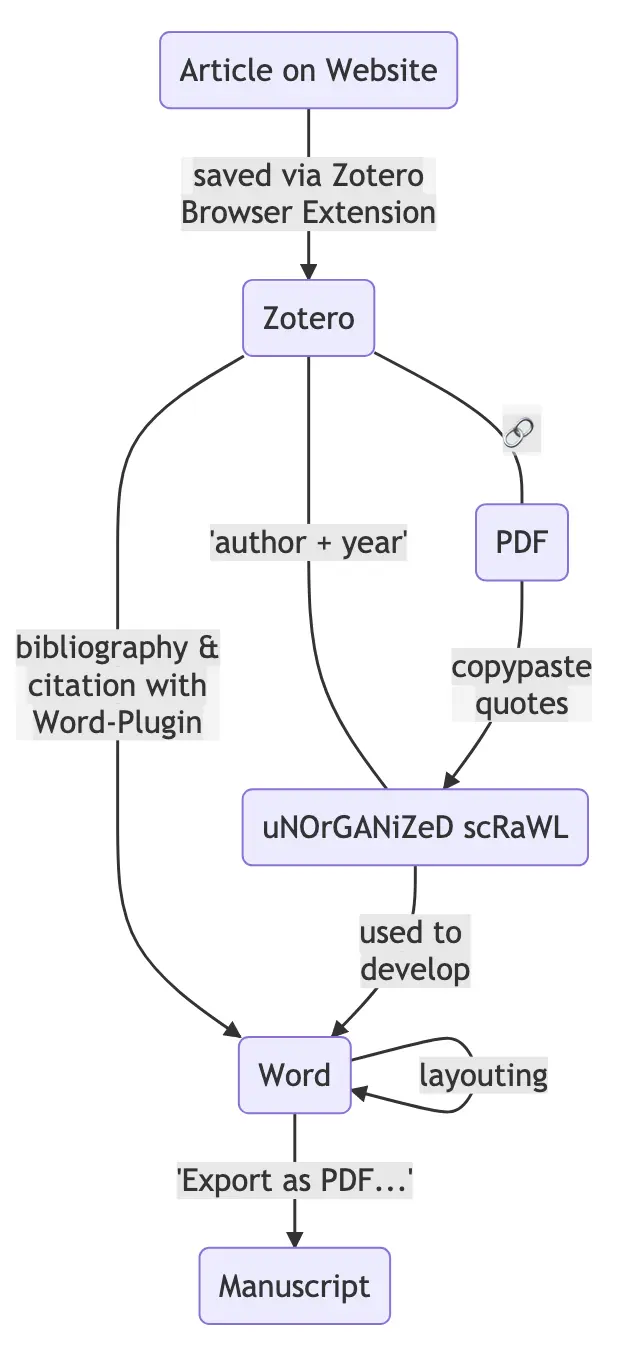

However, the outlined workflow is not only a very generalized version, but quite idealized. The “average” researcher, mostly far from being power users, will often have a much simpler version. Let’s imagine such a less tech-savvy academic, who still uses Microsoft Word. In addition, that person uses a reference manager (let’s say Zotero), and uses the builtin plugin for Word Citations and the Zotero Browser extension, because those two tools are quite easy to use and are “officially” provided/advertised by Zotero. In their case, the workflow from reading to writing should look something like the graph to the left.

Apart from the lack of a dedicated note-taking system, quotes and information from PDFs are mostly copy-pasted, and the unorganized notes (e.g. a long list of bullet points in a separate document 🥶) will contain author and year of the reference. While this is an “implicit” link to the entry in the reference library, this is far from perfect (e.g., ambiguity when there are two papers by the same author in the same year).

Another thing to note is that the missing link between the unorganized scrawl and the PDF makes going back to the context of a quote rather tedious: our “average” researcher will open up Zotero, search for the respective entry, and then open the PDF. Also, working on multiple devices gets quite complicated since Zotero and PDFs may both for themselves sync between devices, but keeping the link between them is definitely a struggle without further plugins.

Nevertheless, this workflow does accomplish some things well: using the first-party Zotero tools, articles are easily saved and citations are easily inserted. The compiling of the final document is particularly easy, since using the Zotero-Word-workflow enables to export the draft as PDF with just a few clicks.

The Zotero-ZotFile-BetterBibTeX-MDNotes-Obsidian-Pandoc version

Now many people here and especially power users dislike Word and would prefer to write in Markdown. As (on average) technologically more adept users, they want to automate tedious tasks like copy-pasting quotes. In addition, they use have a note-taking system like Obsidian. Following the much-mentioned Zotero-ZotFile-MDNotes-Workflow and adding Pandoc, their system is more sophisticated and should look like this.

Compared to the simpler Word-Zotero-Workflow, this has many advantages:

- Note Extraction works like a charm when automated via the MDNotes plugin by @argentum

- Files are organized smarter via the ZotFile Plugin (e.g. automatic renaming). Also syncing PDFs across machines becomes much easier, as you can define separate file storage locations with ZotFile (but to keep the Zotero-PDF-Link is yet another story).

- A reference document combined with Pandoc saves time layouting.

- The BetterBibTeX Plugin enables the use of citekeys which are basically unique and unambiguous identifiers that link notes to the reference library. Using the Obsidian Citations Plugin by Jon Gauthier, citations can be inserted into Obsidian during note-taking and writing. (A smart renaming pattern is to use citekeys, as the PDFs are linked to the reference library entry via its filename – it’s hard to get more future-proof than with filenames.)

However, there are also some disadvantages:

- The most common method of using Pandoc is its Command Line Interface (“CLI”), which is daunting even to some tech-savvy people.

- Zotero, with a bunch of plugins and with a high number of references becomes a bit quite sluggish. (I had 5 plugins with ~3500 references, and Zotero took quite a while to start up.)

- BetterBibTeX is the bottleneck for getting citekeys and the

.bibLibrary file, which you need for Pandoc and for the Pandoc Compiling of references (without citekeys and a BibTeX Library, you cannot use Pandoc for citations). Using BetterBibTeX is in my view the weak point of this workflow: since the.bibfile and the citekeys are basically an extra layer on top of Zotero, they have to be kept in sync. Sync issues are mostly only mildly annoying, but still created the need for yet another plugin to deal with them. - The “fragility” of the Zotero workflow should become clear when you look at

syncing across devices: The Zotero libraries must be kept in sync, but the

.biblibraries BetterBibTeX created by Zotero must be kept in sync as well – as do they need to stay in sync with the respective Zotero libraries. So to keep Zotero and BetterBibTeX libraries in sync, you have to do go deep into obscure hidden plugin settings to set short autopin delays of citekeys and also in the worst case even install yet another plugin to simply deal with inconsistent/duplicate citekeys. Imagine working from somewhere with unstable internet connection and having to keep four libraries in sync. Also, try explaining autopin delays to less tech-savvy people and watch how they run back to Microsoft Word. You get the idea. - On a meta-level, the workflow also has the drawback that its parts are very interdependent, meaning certain components are highly dependent on the others. The Zotero plugins obviously require you to use Zotero. On the one hand, this means that they must be developed in sync to Zotero (i.e., you cannot use some plugins for a while with the new Zotero). On the other hand, this means that Zotero+Plugins constitutes an integrated ecosystem, which are known to produce a certain degree of lock-in: you get them only as a package. If you want to replace BetterBibTeX, you will have to also replace Zotero or Pandoc.

The Zotero-MDNotes-Obsidian Workflow. (The graph is unfortunately mirrored, since mermaid.js weighs stuff differently here.)*

Decomposing the workflow into subtasks

As I stated before, my solution to several problems is/was to leave Zotero. Leaving Zotero can be explained by the fact, that for a lot of functionality, you actually do not use Zotero, but rather the layer on top of it created by its plugins.

So, by working directly with the .bib file, you would practically “cut out

the middleman” (Zotero) in this scenario. But as the aforementioned tools form

an integrated ecosystem around Zotero, replacing the weaker parts (BetterBibTeX

and Zotero) means that you must also look for replacements the better parts

(MDNotes, Zotero Browser Extension).

So to approach this challenge, it is basically necessary to decompose the generalized workflow into subtasks, for which you can find individual tools. The goal would be to find a set of tools that works with little friction, but also does not lock you into one ecosystem, as any lock-in would leave you with sub-optimal solution to certain subtasks.

*The BibTeX Library is the central point of interaction – not Zotero.

The way I see it, the generalized workflow from reading to writing includes the following subtasks:

- Organizing references – usually solved by a reference management app

- Saving references – a.k.a. “get the paper from the browser page into the reference manager without entering everything manually”.

- Linking PDFs, reference entries, and citations – ideally in the most future-proof way

- Extracting Annotations/Notes from PDFs – the effort of copy-pasting only facilitates unorganized scrawls instead of organized notes.

- Citation Picker for automatic citations – we really do not want to type out everything or switch between reference manager and writing app.

- Bibliography Creation – we want to automatically generate the bibliography found at the end of a paper.

- Compiling Markdown with Citations – basically Pandoc with

--citeproc, but we would very much like a simpler solution than a CLI.

Overview: tools for the individual sub-tasks

Instead of simply presenting my set of plugins/tools, I will rather lay out an overview of tools for every subtask. The main reasoning behind this, is that I use the launcher app Alfred for the most part, and Alfred is unfortunately a Mac only app. In addition, I think you everyone would get far better results when customizing the tool set to their own individual needs anyway. For those interested, I will conclude this post with a brief outline of my own workflow.

1. organizing references

Reference managers are the most straightforward part, since basically all

researchers should already be familiar with them. For this reason, I will not

repeat the overviews of reference management apps already done elsewhere, but

focus on reference managers that work with .bib files needed by Pandoc.

Reason is, that Pandoc is pretty much the only compiling tool we have when we

want to convert Markdown with citations to Word or PDF.

I will also forego the solutions that only export to the .bib format, since

exports without live-syncing of a library with the BibTeX-File (like

BetterBibTeX does) makes it impossible to use a citation picker’s with a .bib

that is not reflecting “live” your library (point #4). And if you use use a

citation picker that does not work on .bib files (e.g. Zotero’s Word Plugin),

you won’t be able to use Markdown/Pandoc (point #7). So for a workflow with

automatic citations/bibliography in markdown more or less requires a reference

manager working on BibTeX (or at least one live-syncing to a .bib – although

this will have the pitfalls like BetterBibTeX’ syncing issues).

Regarding reference managers working on BibTeX files, the field is actually rather small. To my knowledge there are:

- Name giver BibTeX, which is part of most LaTeX distributions. It only works from the command line.

- Zotero with the BetterBibTeX Plugin.

- BibDesk, an Open Source reference manager by the makers of PDF Reader Skim. Mac only.

- JabRef, a javascript-based, Open Source reference manager that. Available cross-platform. (Zotero users may know JabRef from this page where BetterBibTeX redirects you for Citation Key explanations.)

Note that both, BibDesk and JabRef can automatically rename and move PDFs.

This means either of them are basically equivalent to Zotero + BetterBibTex +

Zotfile.

2. saving references

There are also tons of other solutions, but again, I will limit the list to the ones that can be used with the BibTeX format.

- Independent from any individual reference manager, Bib It

Now!

stands out as a feature rich extension for Chrome and chromium-based browsers.

Generates high-quality BibTeX-Entries which can be copypasted into most

reference managers (not only the ones mentioned above).

- Yes, a less known feature of many Reference managers is that you can just copypaste BibTeX-text into the reference manager to generate the a proper entry. :)

- There are numerous other small browser extensions, but the quality of BibTeX-Entries they provide is rather low compared to Bib It Now!.

- The Zotero Connector, available for different browsers, but obviously only working with Zotero. Does a pretty good job.

- The JabRef Browser Extensions, basically the same as the Zotero Connector, but for JabRef. Haven’t tested it much, but does the job.

- DIY-Solution: Use DOI Content Negotiation. It is actually surprisingly easy, and the fact that it can run on one line of shell code means it is extremely easy to incorporate in basically any tool that allows scripting. (Alfred Workflow, Keyboard Maestro Macro, etc.).

curl -sLH "Accept: application/x-bibtex"

3. linking PDFs, reference entries, and citations

The simple solution for this is to simply use author & year manually. The

proper solution to avoid complications (e.g. multiple publications by the same

author in the same year), is to either use some sort of hyperlink, or to use a

unique identifier like the citekey.

- MDnotes+Zotfile use the Zotero URI Scheme to deeplink to the PDF on the respective page

- Another solution is to use the file URI

Scheme

file://to link to a file. - BibDesk also has its own URI

Scheme which is smartly

implemented as in the form

x-bdsk://, making it so easy to automate that I am wondering, why I am the only one who used that ( in my Pandoc Alfred workflow). - For all intents and purposes, the very act of using BibTeX already implies using citekeys as unique identifiers. Any citation in a draft or in the knowledge base, which uses the citekey, will already have an unambiguous “link” to a reference library entry. Using the automatic renaming functions, which are offered by basically all reference managers (in case of Zotero with ZotFile), you can also prepend citekeys to PDF filenames, ensuring in a very future-proof way that you can always associate a citations with a PDF.

4. extracting Annotations/Notes from PDFs

As this step does not require the BibTeX-format, there are far more options here. The only requirement for the apps and plugins listed below was that they can export the annotations as Markdown.

- ZotFile + MDnotes, the Zotero Plugins, have a lot for formatting options, and can distinguish multiple highlight colors.

- DocDrop, a Web Service based on Hypothesis, seems to be still in its infant version.

- PDF Expert, an app from the developer team Readdle. It is Mac only, has Markdown Export, and is also a pretty solid and popular PDF Reader. It’s available for a one-time payment, which does cost a bit. However, they offer a 50% educational discount for researchers. Unfortunately, like all apps from Readdle, the app has rather poor support for automation.

- Highlights, a PDF reader dedicated to making annotations and getting them easily out. The most noteworthy feature should be you can annotate images, that are exported with the other annotations. Unfortunately, it is Mac/iOS only, and also only available via subscription-based payment.

- The Obsidian Plugin Extract PDF Highlights. Obviously has great Obsidian integration, but the annotation formatting options are rather simple last time I checked.

- sumnotes is a Web service that allows you basic annotation extraction. It works on a Freemium model, meaning that you can get 100 annotation (or something like that) for free, otherwise you have to subscribe to their service. Should be useful for doing some quick annotation extraction on someone else’s devices.

- Readwise, the well known service for collecting highlights from different sources. They offer an official Obsidian Plugin. They are a subscription-based service, and also are rather used for eBooks or Kindle Book, rather than PDFs.

- Memex and Hypothes.is are free annotation extractors, that mostly focus on annotating the web. There is a step-by-step-guide for Readwise and Hypothes.is.

- Highlighted, an iOS only App which is used to OCR highlights from offline Books (those things printed on paper). It has Markdown Export options and you can get some bibliographic informative by scanning the ISBN barcode of the book.

- pdfannots, a pyhton-based CLI which runs on pdfminer.six as its engine. Its use requires a bit of technical knowledge, but it has some useful extraction options like a setting for the number of columns per page.

- PDF Annotation Extractor a workflow for the launcher App Alfred. It’s basically a GUI for pdfannots with many automation and formatting options. And it has Obsidian integration and builtin prepending of a YAML-Header. And I love the fact that it is can merge annotations that span across pages and that it is only one-click from the PDF to the extracted annotations in Obsidian (Disclaimer: It’s developed by me. 😉). Drawbacks are that it is unfortunately Mac only, because Alfred is Mac only. Furthermore, multi-color highlight are not recognized and (for now) only commented highlights and free comments are extracted.

- Obsidian Annotator, an Obsidian Plugin based on Hypothesis which directly extracts annotations to an associated markdown document. Its features include a pretty nifty linking of annotations with specific PDF sections. Its major drawback, however, is that you have to read the PDF in Obsidian itself — it does not work with external PDF Readers.

- DyAnnotationExtractor, a JavaScript-based CLI (haven’t tested it yet)

- Skim to MD Notes for users of the PDF Reader Skim (which tends not to work well with other Annotation Extraction Solutions, since it doe snot store annotations in the PDF).

- Databyss a academic Word Processor & Note Taking app which is also able to extract annotations

5. citation picker for automatic citations

Citation Pickers should be compared based on two criteria 1. from which

library format (Zotero, BibTeX/.bib, etc.) you can call the picker, and 2.

into which app you can insert the citations.

- Zotero has built-in plugins to insert citations into the three most common word processors Word, OpenOffice, and GoogleDocs. In this case, you use the Zotero library (“from”) and have three options regarding which app you want to insert the citation into.

- When writing in Obsidian, you can use the Obsidian Citations

Plugin to insert from any

.bibfile. - More established text editors for Programming also have citation picker plugins. For example Citer for Sublime Text 3 or Autocomplete BibTeX for Atom. (Auto-Complete being a “simpler” version of a citation Picker. )

- Zotpick allows to insert Markdown citations into any app, but unfortunately only works when used with Zotero and BetterBibTeX. Only runs on Mac.

- Zotero Citation Picker for Windows is a Citation Picker for Zotero that only runs on Windows (duh!). It also relies on BetterBibTeX.

- ZotHero is an Alfred-Workflow for Zotero, which also features citation picking in different citation styles and in Pandoc-style.

- Zettlr has a built-in citation picker, which use Zotero or BibTeX formatted libraries, but is only able to insert into Zettlr itself.

- Using the Pandoc Suite for Alfred

(Mac only), you can use get citations from any

.bibfile and input them into any other app. Also has the most bonus functionality (opening a link directly from the picker, emailing full bibliographies of one entry, etc.) (disclaimer/proud to say: I am the developer). - DIY Solution: You can simply use an internal URL provided by BetterBibTeX to trigger a native Zotero Citation Picker from anywhere. As with DOI Content Negotiation, this is a very simple solution, which unsurprisingly has been implemented for some editors like Scrivener, vim, or Atom.

http://127.0.0.1:23119/better-bibtex/cayw

6. bibliography creation

The options here are fairly limited, since the only method of getting citations from a markdown document into a compiled Word or PDF file is Pandoc – the alternative being the Word processor plugins from reference managers like Zotero, which requires writing in Word, OpenOffice, or GoogleDocs (which we didn’t want to do in the first place).

However, there are two very noteworthy tools that approach bibliography creation from a totally different angle, namely the two Pandoc Filters url2cite and Manubot-Pandoc-Filter (part of the Manubot Project). Instead of saving an article in the reference library and then using a citation picker to cite them in the writing app, you directly use an identifier like the DOI or URL with a pseudo-pandoc-markdown-syntax to insert them directly into the draft. The promo screenshot from Manubot to the right explains the approach probably better than words can.

Regarding the generalized academic workflow, this direct-identifier-approach basically works by skipping reference managers entirely, skipping subtask #1 (saving reference), subtask #2 (organizing references), #3 (linking references), and #5 (citation picking).

However, there is also the drawback that you use reference managers for a reason: organizing references for later use. When you want to use a reference two papers later again, a reference manager is still the way to go. Furthermore, identifiers in itself aren’t very useful for disciplines where author identities matter (mostly social sciences & humanities). Nevertheless, the extreme ease of use of this approach makes it too tempting to not at least use it for one-off-citations for which you are certain that you will only need them for one paper.

7. compiling markdown with citations (Pandoc)

As mentioned before, there is no way around Pandoc for compiling Markdown documents with citations. There are, however, multiple methods of actually using Pandoc, many of which are more user-friendly than using the Terminal.

- Pandoc “Vanilla”: The Basic Command line interface. The following syntax is

the minimum for converting markdown with citations. The

cslfile can be downloaded from the Zotero Style Repository or directly from The GitHub Repository. (Note that usingpdfas output format requires the installation of a separate pdf engine.)

pandoc "path/to/input.md" -o "path/to/input.docx" --citeproc --bibliography "path/to/library.bib" --csl "path/to/citation_style.csl"

- Far easier is the cross-platform menubar app DocDown, which is essentially a graphical interface for Pandoc. As Pandoc is packaged into DocDown, you even don’t need to install Pandoc itself. DocDown requires the same inputs as above, but does provide an intuitive graphical user interface (GUI) for it. However, the customization options are fairly limited, and Pandoc vast capabilities are not really utilized.

- If you are willing to pay, there are also some paid options like Writage that make it more convenient to convert from Markdown to Word

- The Obsidian Pandoc Plugin also provides a graphical wrapper for Pandoc. However, it only works for markdown notes inside Obsidian.

- Zettlr works quite similarly in having integrated Pandoc into the writing app, but has the same drawback of having to open the markdown file from inside Zettlr.

- Yet another GUI for Pandoc is the Pandoc-Suite for Alfred, which only works on Mac (because Alfred is a Mac only app). It comes with a Zotero/BibTeX-Citation Picker and automates a lot of stuff, providing a one-click-solution to convert a Markdown document from Finder and some other apps, among them Obsidian. (Disclaimer: Again, I am the developer.)

- The Pandoc-Wiki features a very long list tools for using Pandoc more conveniently.

8. bonus: organizing longform writing

Not strictly part of the workflow discussed here, but a much related issue is the question of how to organize longform writing process itself. The basic approach (“dump everything into one document”) is of course unsatisfactory. However, there are several very different solutions to this:

- The most popular solution is Scrivener, an app specifically developed for organizing longform writing. After finishing a draft in Scrivener, you can simply export as Markdown and then use Pandoc. Unfortunately, Scrivener suffers from the same illness as Microsoft word: no separation of concerns and an unmanageable feature mountain.

- Another quite innovative approach is the outliner-writing-app Gingko which “let’s you write in a tree structure”. That may sound a bit abstract, but watching the demo videos on the website make the idea pretty clear. Gingko’s approach is a bit too modular for my taste, but I applaud the creativeness of the app and assume that there quite a few others for whom the app will work well.

- A recent addition to the Obsidian plugins is the Longform Plugin for

Obsidian, which offers basic compiling

and re-arranging functionality that is similar to Scrivener. It is, however,

still a rather new solution, and some quite essential features like having

sub-chapters are still missing.

- When compiling with the Longform plugin, footnotes are not considered (yet), with the result that they are scattered all over the place. You can use the Linter Plugin to move all of them to the bottom & also re-index them.

- Also relevant to people deciding to write Longform in Obsidian might be

the Obsidian Link

Converter for

converting Image Links, as Pandoc is not able to parse Obsidian’s Image

Wikilinks (

![[ ]]). - You can use this lua filter to remove wikilinks from a Markdown document during conversion.

- For across-note-wordcounts, you can use my Word Count Dashboard which uses Dataview the plugin.

My own implementation of the workflow

This leaves me to conclude with one last mermaid diagram, depicting my very own workflow. As all the tools used have been mentioned in the sections before, little additional explanation should be necessary.